Music semantics refers to the ability of music to convey semantic meaning. Semantics are a key feature of language, and whether music shares some of the same ability to prime and convey meaning has been the subject of recent study.1

Most theorists of music describe at least four different aspects of musical meaning:

- meaning that emerges from a connection across different frames of reference suggested by common patterns or forms (sound patterns in terms of pitch, dynamics, tempo, timbre etc. that resemble features of objects like rushing water, for example)

- meaning that arises from the suggestion of a particular mood.

- meaning that results from extra-musical associations (national anthem, for example)

- meaning that can be attributed to the interplay of formal structures in creating patterns of tension and resolution.

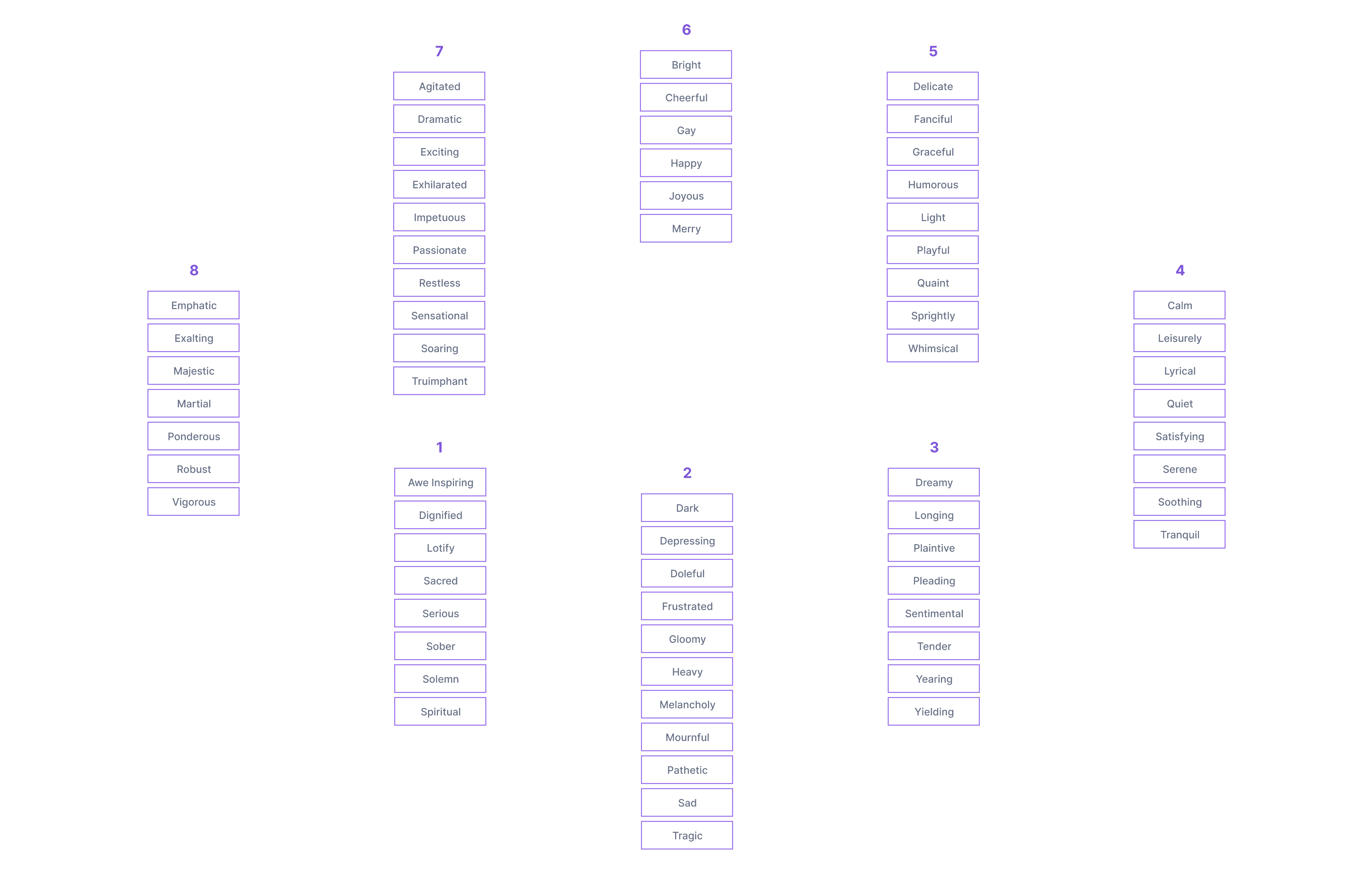

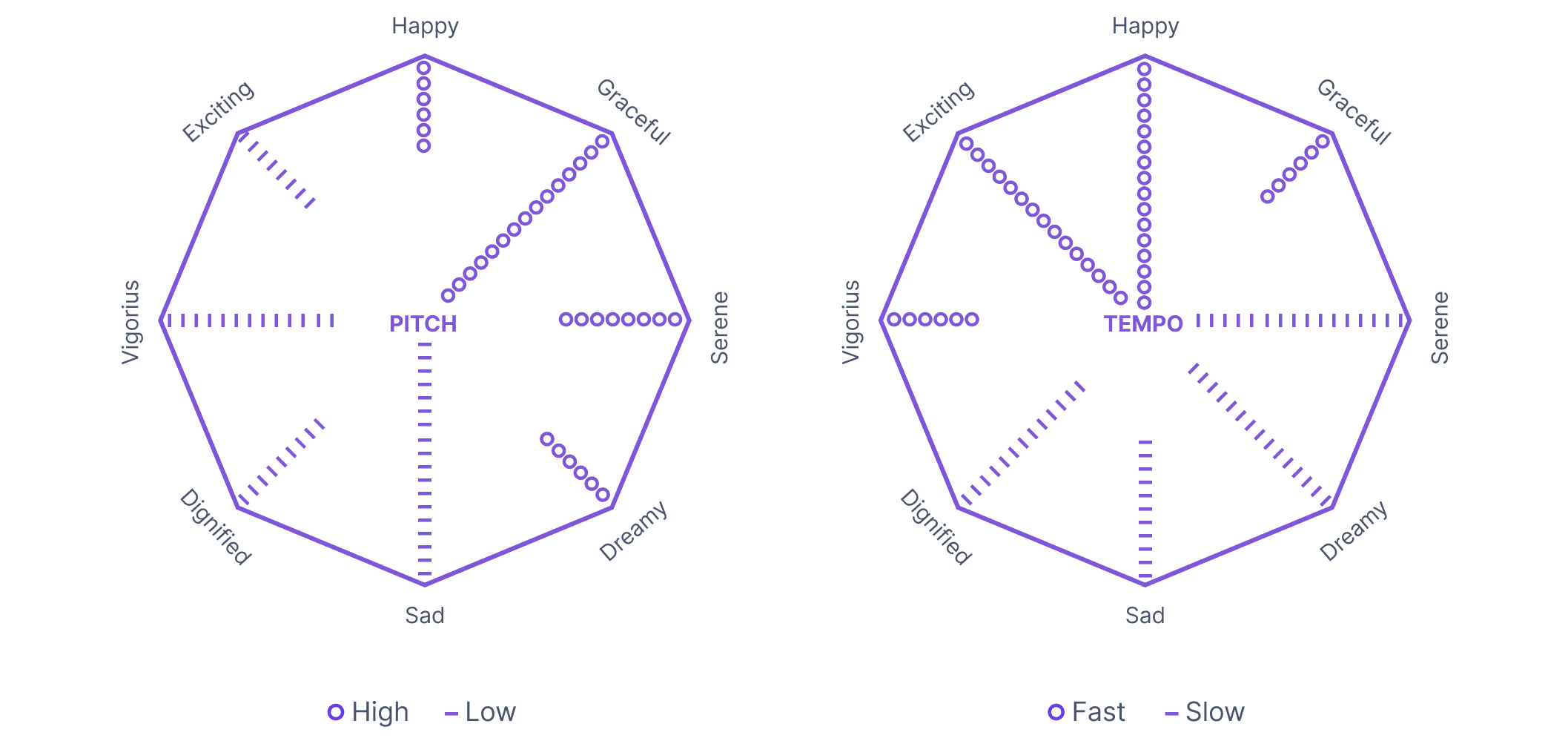

Many have tried throughout the years to establish a direct correlation between certain kinds of music and linguistic semantic meanings. The first documented study that investigates the semantics of music dates back to 1937 and was written by the acclaimed American psychologist and educator Kate Hevner. In The affective value of pitch and tempo in music Hevner tries to measure music expressiveness through a series of experiments. This study is also the summary of multiple papers published respectively in 1936 and 1935 in which Hevner first presents a list of adjectives apt to the description of pieces of music. This adjective list will be known in the years that followed as the Hevner’s Adjective List and will be the main point of reference to this day of direct correlation between certain types of music and emotion connected to it.

In The affective value of pitch and tempo in music, the researcher exposes several University class groups to two distinct musical programs and asks them to choose the corresponding adjective when hearing a specific piece of music. The adjectives are clustered into eight different groups: Happy, Graceful, Serene, Dreamy, Sad, Dignified, Vigorous and Exciting.

Here follows what Dr. Hevner discovers:

“In this series of experiments, pitch and tempo show themselves to be of the greatest importance in carrying the expressiveness in music. Tempo plays the largest part of any of these factors. High pitch shows its largest effects on the humorous-sparkling-playful tone and low pitch divides its effectiveness over sad, dignified, and vigorous-majestic groups. Harmony and rhythm are on the whole less effective than these first three variables, for they show smaller majorities and cover a more restricted range of feeling tone.”

This is the first record of a study that can prove that a high pitched tone is associated with humorous-sparkling-playful adjectives.

Furthermore, Hevner also noticed that “sadness is best expressed by the minor mode, a low pitch and a slow tempo. With dissonant harmonies lending substantial support and rhythm and melody of little significance.”2

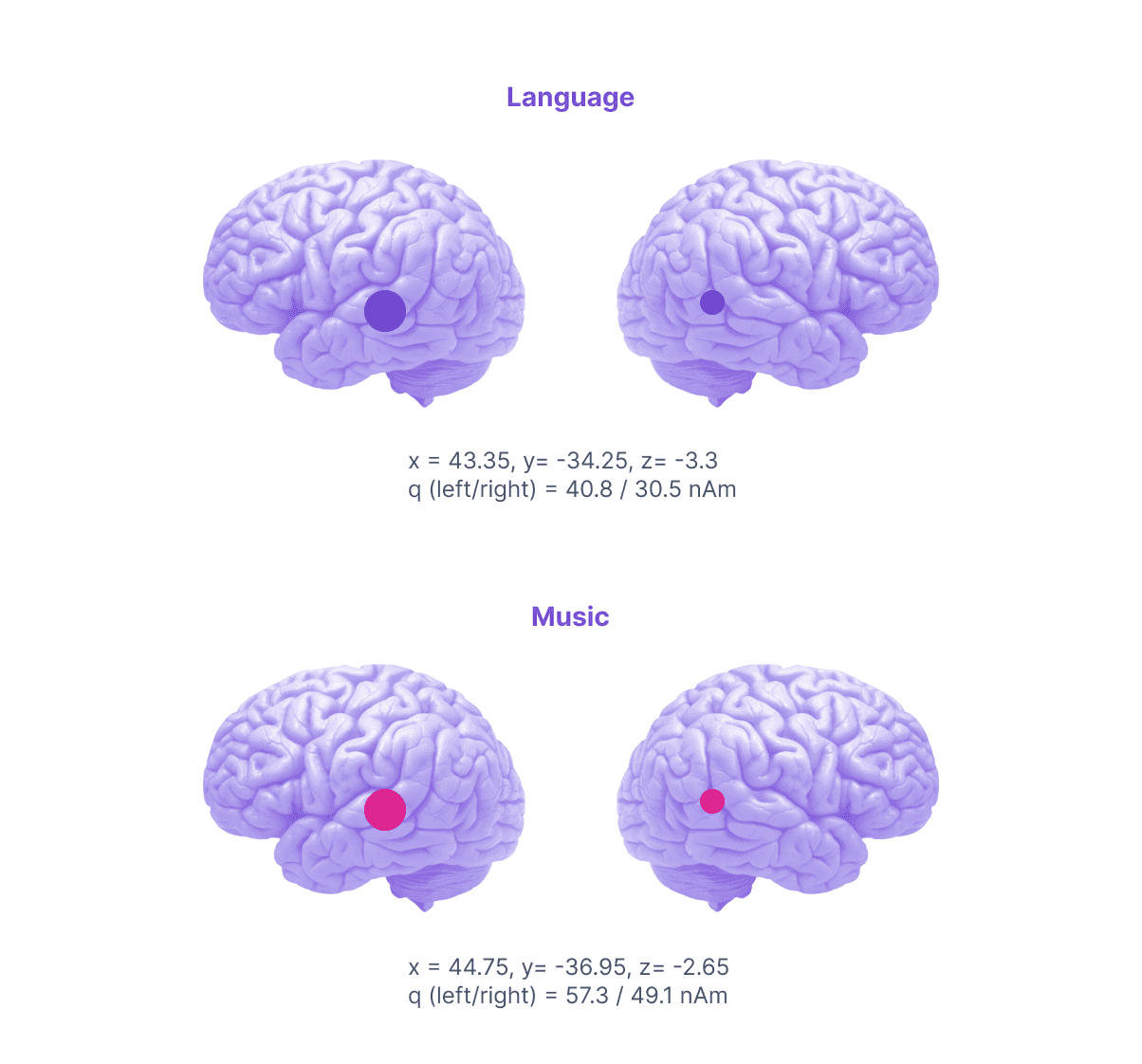

A significant discovery though, was made in 2004 by researchers Stefan Koelsch, Elisabeth Kasper, Daniela Sammler, Katrin Schulze, Thomas Gunter and Angela Friederici in a paper published in Nature magazine called Music, language and meaning: brain signatures of semantic processing.

The researchers set out to experiment whether or not music can activate brain mechanisms related to the processing of semantic meaning. In order to find out they compared the processing of semantic meaning in language and music. In order to objectively establish if music would trigger the same neurologicals semantic reactions, they used an electrophysiological index of semantic priming called N400.

They found that the N400 priming effect did not differ between language and music with respect to time course, strength or neural generators. Their results indicate that both music and language can prime the meaning of a word, and that music can, as language, determine physiological indices of semantic processing.

So if the connection between conveying a semantic appropriate meaning and playing music has been identified as plausible by the studies cited above, how do we conceive music? Is there really something like music semantics?

Mihailo Antovic states that the “cognitive semantics of music” seems appropriate since it turns the question of musical meaning upside down: the issue is no longer whether music has meaning, not even whether listeners project a meaning into music which is itself meaningless; rather, the question becomes what our conceptualization of music can tell us about our conceptual system in general. This shift of approach has provided a sound basis for the foundation of a true musical semantics.3

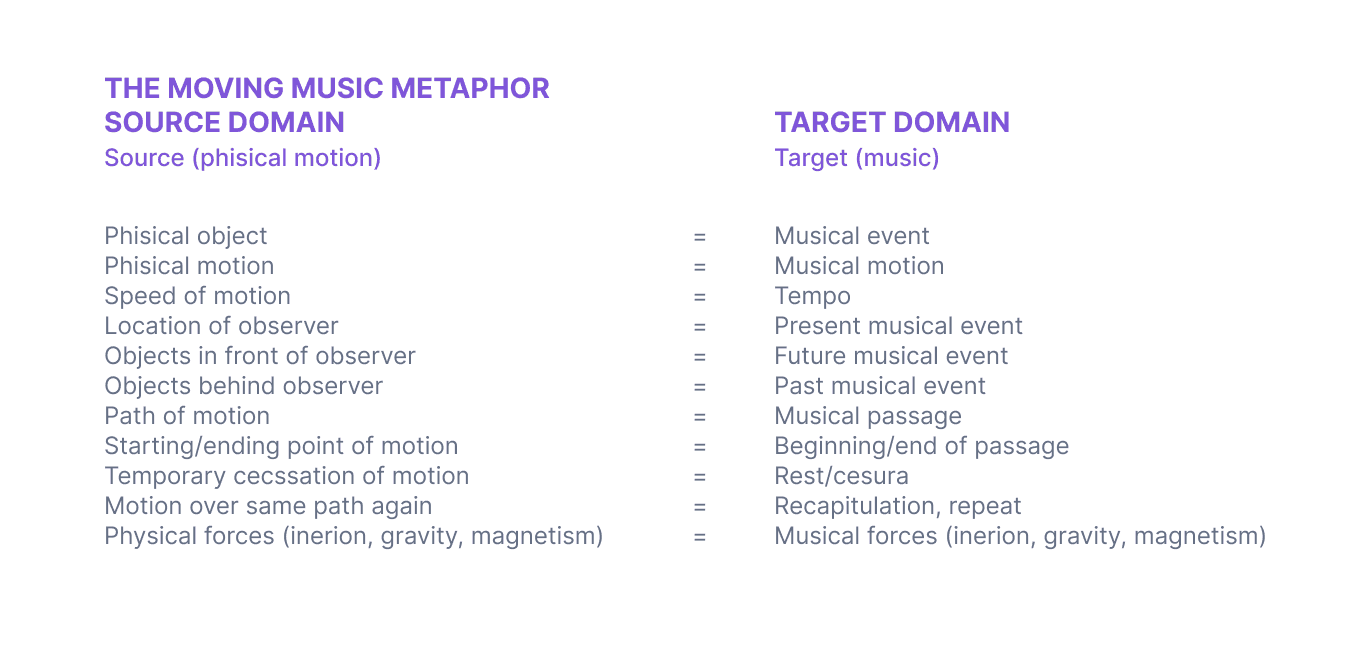

Furthermore, Antovic also states: “whatever way we conceive of music, we metaphorise” and goes on in exploring a study4 from Johnson and Larson carried out in 2003 that approaches the problem of musical meaning from a cognitivist perspective. Antovic says: “For them [Johnson and Larson], three typical metaphors westerners use to conceptualize music include Musical Motion, Musical Landscape, and Musical Force. The novelty in this paper is their use of Lakoff and Johnson’s cross-domain mapping to explain the grounding of such metaphors. This seems to be the first analytical system from a linguistic semantic theory that works in the domain of music.

This is especially interesting when we look at the image below because “whenever we say things like ‘‘The strings slow down now’, or ‘The music goes faster here’, we actually visualize this music as a series of physical objects moving through space at different speeds. The physical (motion) is related to the abstract (music), the source domain maps onto the target, and musical conceptualisation is fully accorded with Lakoff and Johnson’s system.” 5

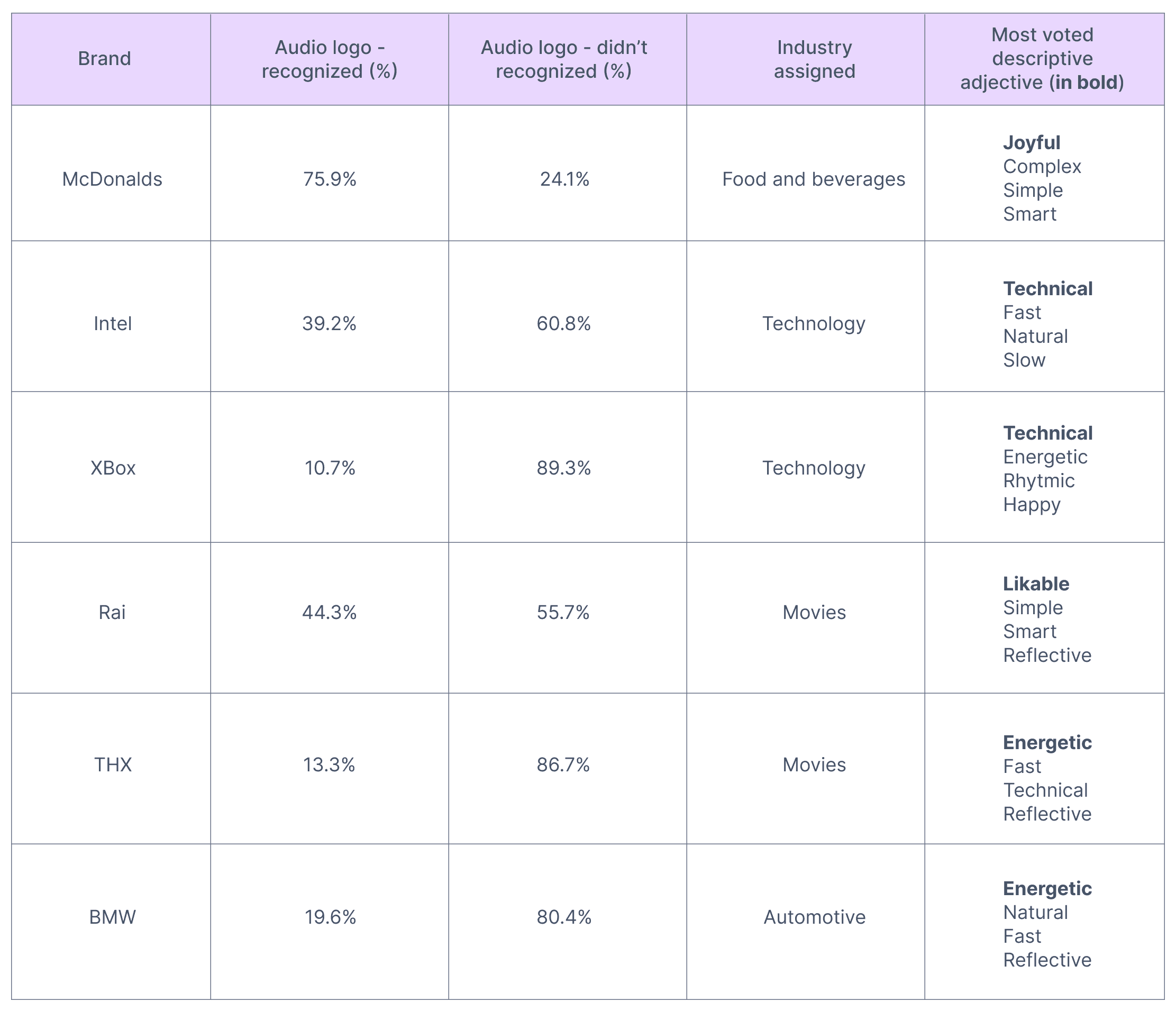

An interesting study on the effectiveness of music semantics in music branding has been conducted by myself and the following Politecnico di Milano students Jacopo William De Denaro, Arianna Dipollina, Alicia Invernizzi and Alessandro Vergani during the Bachelor Metaprogretto course at Communication Design at the School of Design in 2016. The study was called Audio branding. Identità sonora nelle marche and had the following structure. After analyzing the state of the art music branding in 2016, we sent out an online survey that asked 282 respondents in Italy to listen to several audio logos. Inside the survey participants were asked to recognize the brand associated to a specific audio logo, establish a category in which they would feel the audio logo belonged to (choosing from automotive, food and beverages, movies and technology) and assign an adjective describing the emotion they would have most likely associated with the audio logo (choosing from a variety of adjectives that would change based on the audio logo). In the following table here the result of the study:

It is important to notice that the majority of the people we interviewed and talked to could identify the industry related to the specific sound, but could not recall the exact name of the brand/or the correct company.

E.g. The THX sound was 100% associated with movies, but the majority of people couldn’t tell what brand it was from. Same happened with the BMW sound, mistakenly associated with other car manufacturers.

The study tried to deep dive in acoustic brand recall/recognizability and semantic association of adjectives to music.

Lastly, I want to close this paragraph citing an extensive study carried out and published in 2020 by researchers Lepa, Steffens, Herzog and Egermann. In Popular Music as Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking of Previously Unknown Music the authors confirm that indeed music carries a semantic meaning within its own genre and characteristics. They were able to establish solid correlation between what was being played to different participants and how they perceived the music track. They could also confirm that music is able to convey similar semantic meaning although being played to different generations of people in different countries.

Moreover they “exhibit that music is such a stable, non-verbal sign-carrier that a machine learning model drawing on automatic audio signal analysis is successfully able to predict significant proportions of variance in musical meaning decoding.”6

Conclusion

In synthesis: researchers seem now to agree that music bares semantic meaning to whomever listen to, thus enabling creatives and musicians to take advantage of the scientific knowledge in Music Semantic and Music Perception in order to design better sounding, greater meaning-conveyer sonic tracks for the brands of the future.

In this paragraph several studies have been presented to the reader in chronological order with the goal of tracing a brief history of scientific process in Music Semantics. The next paragraph will focus on Music Psychology and more importantly on how humans perceive music.

Hevner, K. (1937, October). The affective value of pitch and tempo in music. The American Journal of Psychology, 49(4), 621-630.

Antovic, M. (2009). Towards the Semantics of Music: the 20th Century. Language and History, 51(1), 119-129.

Mark, J., & Larson, S. (2003). Something in the way she moves: metaphors of musical motion. Metaphor and Symbol, 18(2), 63-84.

Antovic, M. (2009). Towards the Semantics of Music: the 20th Century. Language and History, 51(1), 119-129.

Lepa, S., Steffens, J., Herzog, M., & Egermann, H. (2020). Popular Music as Entertainment Communication: How Perceived Semantic Expression Explains Liking of Previously Unknown Music. Media and Communication, 8(3), 191-204. 10.17645/mac.v8i3.3153