We're immersed in a sea of air. Snapping fingers, speaking, singing, plucking a string, or blowing a horn cause a vibration in the air near the source of sound. As a spherical wavefront, a sound wave moves outward from the source. It's a longitudinal wave in which the air pulsates in the same direction that the wave moves. Waves on a stretched string, on the other hand, are transverse waves because the string's motion is perpendicular to the wave's travel direction. 1

In this ocean of air, sound waves pass by, causing components of our ears to vibrate in the same way as the sound source. Reflections from the ground and other things confound what really reaches our ears. Much of the sound we hear in a room is reflected off the floor, walls, and ceiling before reaching our ears. Also, what we hear weakens with distance from the source and the strength of the source wave is dispersed in the environment.

Waves are emitted by physical vibrant objects such as a violin when a string is plucked or a bell when it is rung. Whenever this happens, waves begin to travel, but they cannot be called sounds yet. These waves trigger a vibration in the eardrum (or tympanum) and the brain perceives sound. The perception of sound includes, but it is not limited to the ear as an organ. We can actually hear low frequency sounds (from 1Hz to 20Hz) in various regions of the body.

"The perception of sound includes, but it is not limited to the ear as an organ. We can actually hear low frequency sounds (from 1Hz to 20Hz) in various regions of the body."

Furthermore, we can perceive visual manifestations of sound too. At very high intensity sound can move or even destroy objects such as windows. Not only this, but also we can “see” sound if we think of how speakers move when they are playing music, and we can also “feel” sound with our own body if we are very close to a subwoofer speaker in a club. In this case, if the music is loud enough, we could perceive how air is moving and impacting our body.

Now a question comes very spontaneously: can we hear all sounds? What is the actual human auditory range?

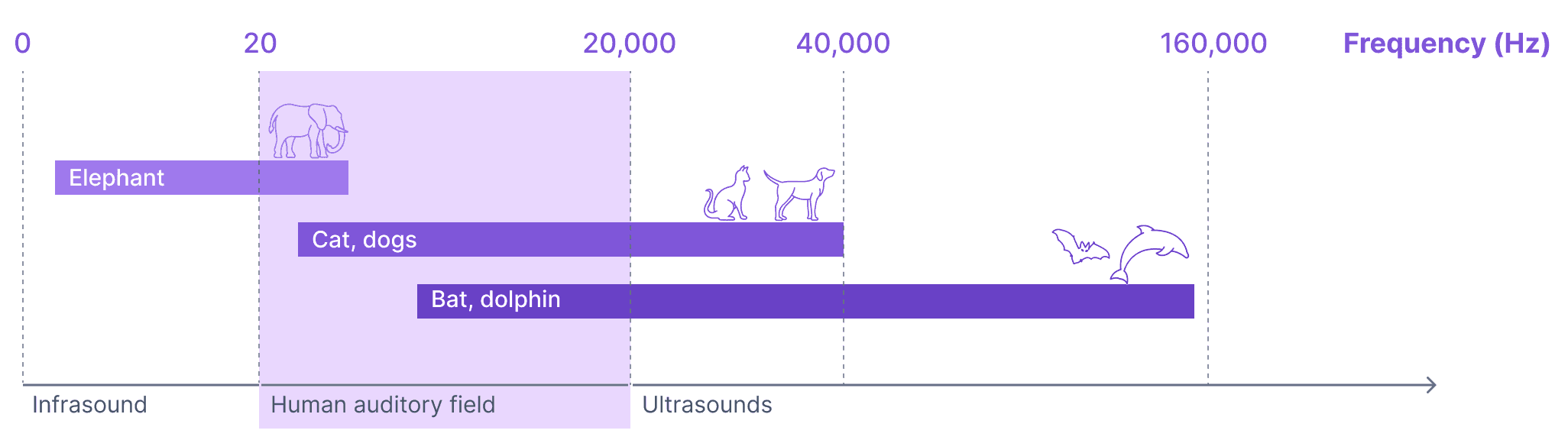

Frequencies between 20 Hz (lowest pitch) and 20 kHz are perceived by the human ear (highest pitch). Although certain species (such as the mole-rat and elephant) can detect infrasounds, all sounds below 20 Hz are classified as infrasounds. Similarly, all noises over 20 kHz are ultrasounds, however there are sounds for a cat or a dog (up to 40 kHz), as well as a dolphin or a bat (respectively up to 40 kHz and 160 kHz).

Sound is perceived differently by every human being. And sound can be modified or recognized differently based on several different factors that contribute to its modification.

The field of study that takes care of physical measurable properties of sound waves, with their amplitude and frequency, and that takes in consideration also subjective phenomena such as volume and tone, is called Psychoacoustics. The study of Psychoacoustics varies widely from technical and physical demonstration of sound to human, emotional and cultural aspects of sound. Here’s the definition from The Sense of Hearing by J. Plack 2:

Psychoacoustics links our world of acoustics to how we perceive sound. It comes from the word Psychology and Acoustics. The aim of this field of research is to describe how we perceive sound with mathematical functions and models. The goal would be to define models that describe how we perceive sounds. This practice links the acoustics of sound (physics) to how we perceive it (psychophysics).

The threshold of hearing

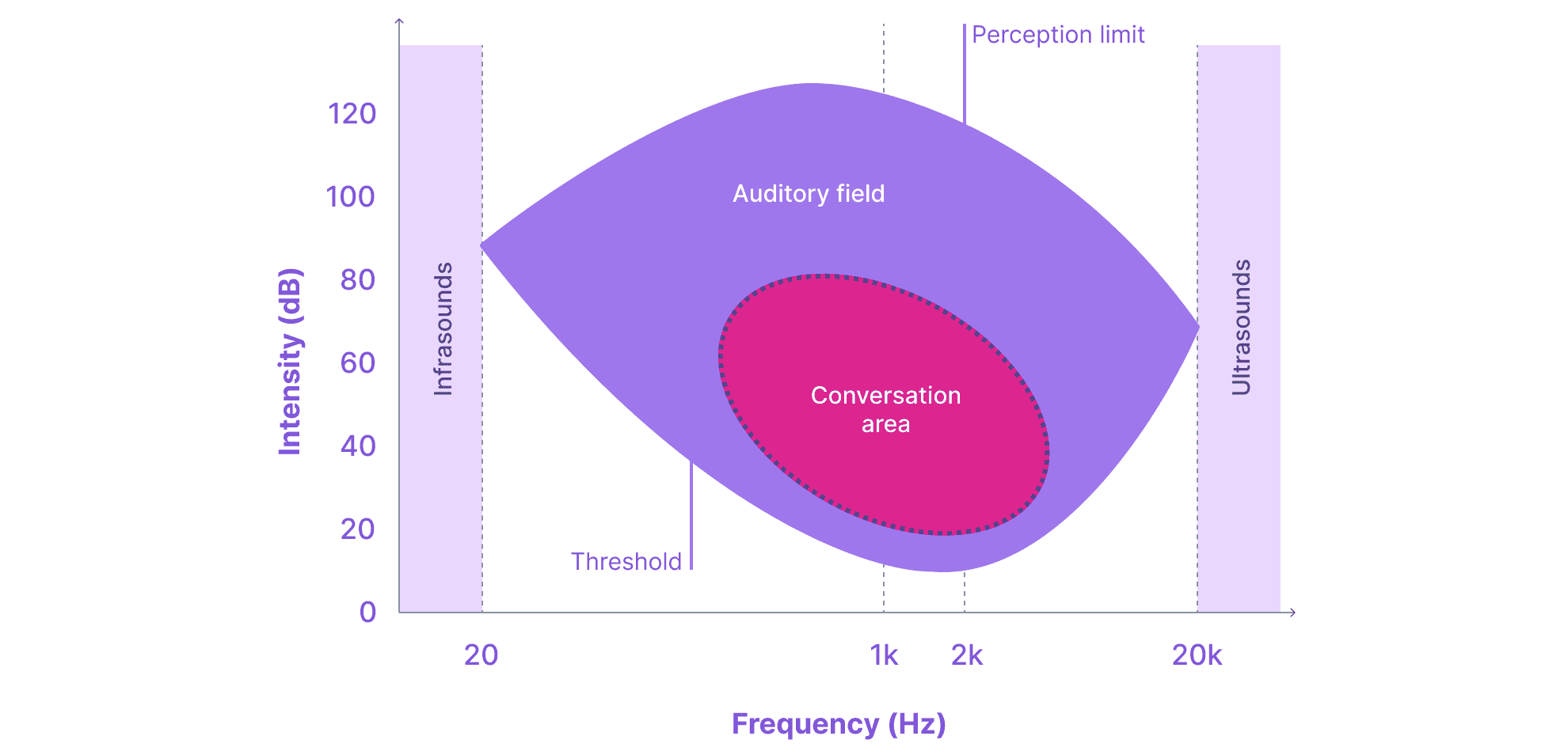

The hearing threshold is the absolute lower limit of the auditory system. It indicates which are the sounds that are so faint we can barely hear them.

Our sensitivity threshold varies at different frequencies between 20 Hz and 20 kHz. The optimal threshold is close to 0 dB (at roughly 2 kHz). It is also in this middle range of frequencies that the sensation dynamics is the best (120 dB). The conversation area demonstrates the range of sounds most commonly used in human voice perception; when hearing loss affects this area, communication is altered.

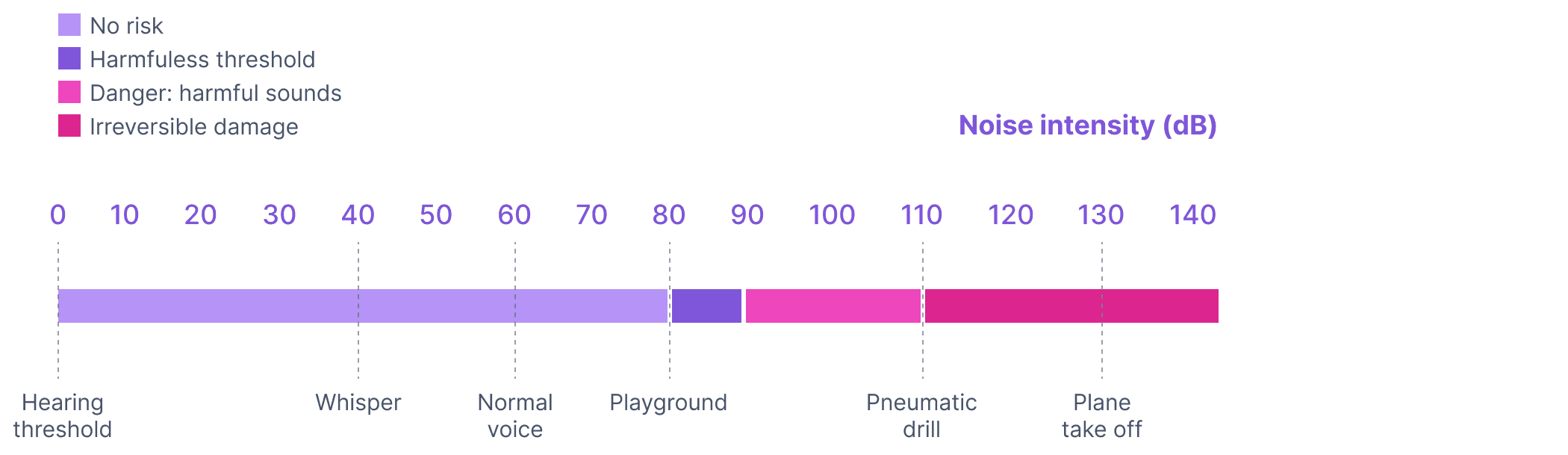

Dynamic Range of sound

The dynamic range of the human ear is 0dB (threshold) to 120-130 dB. This is especially true in the mid-frequency band (1-2 kHz). The dynamic is narrowed at lower and higher frequencies. However, as illustrated, all sounds above 90 decibels cause damage to the inner ear, with 120 decibels causing irreversible damage.

Auditory masking

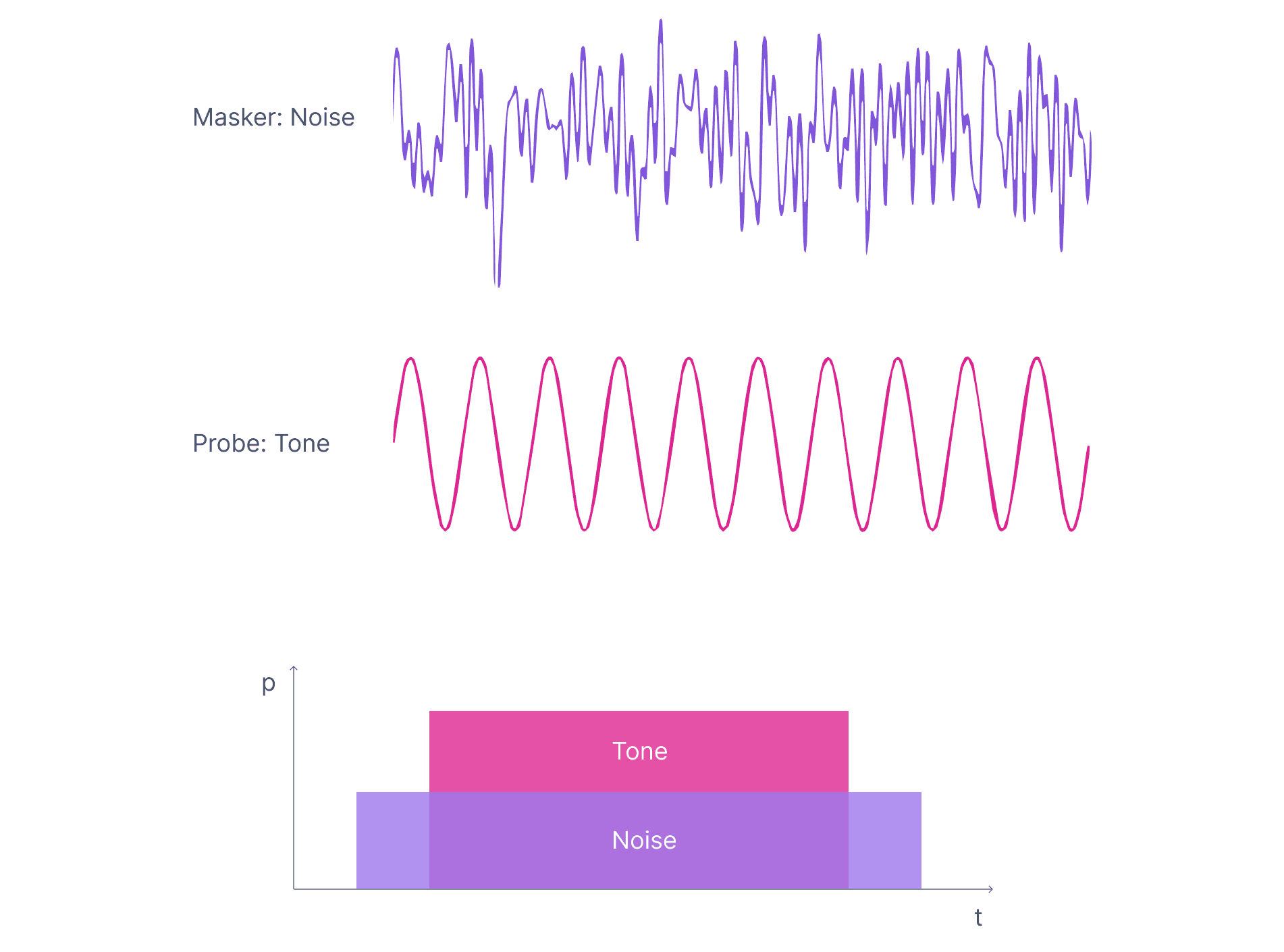

Masking occurs whenever the activity produced on the basilar membrane by one sound (the masker) **obscures the activity produced by the sound you are trying to hear (the signal). If the masker and the signal are far apart in frequency, then the masker will have to be much more intense than the signal to mask it. If the masker and the signal are close together in frequency, then the masker may have to be only a few decibels more intense than the signal to mask it. 3

Auditory masking refers to “hearing out” one frequency component in the presence of other frequency components. It is fairly simple to assess when we are able to hear a certain sound in total silence. Nevertheless, when other sounds come into play, it becomes more difficult. These sounds are called “masking sounds”.

In the masking experiment a white noise sound and a tone sound are mixed together and a person is asked to detect whether or not can hear the tone when the two sounds are played together. This is useful in order to get to know what is the auditory masking threshold of this particular experiment.

Binaural masking

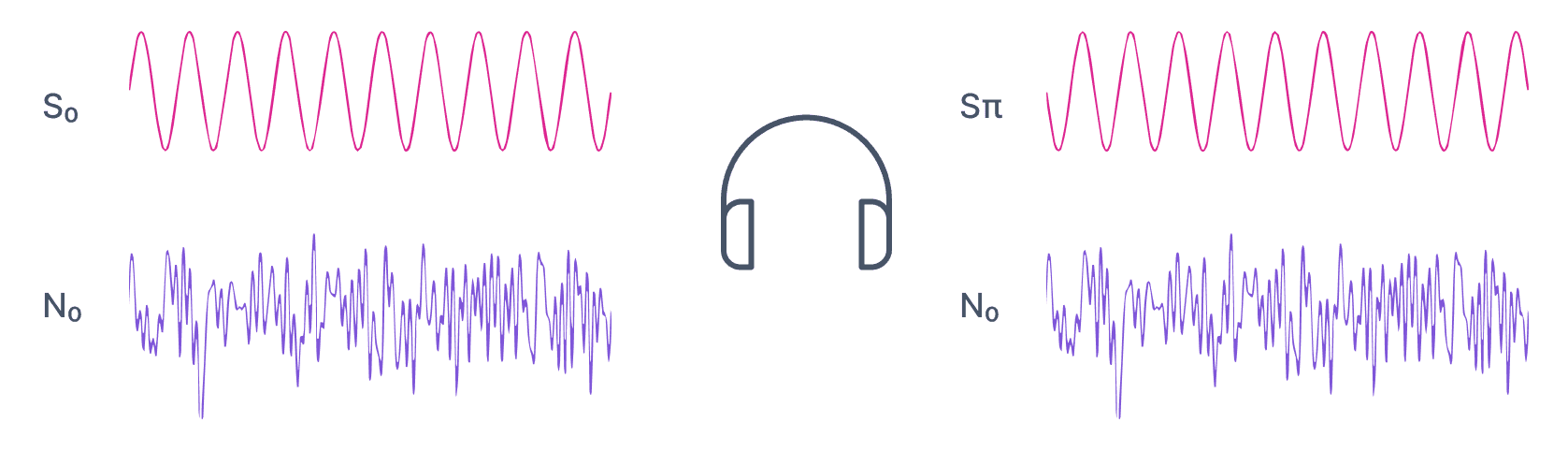

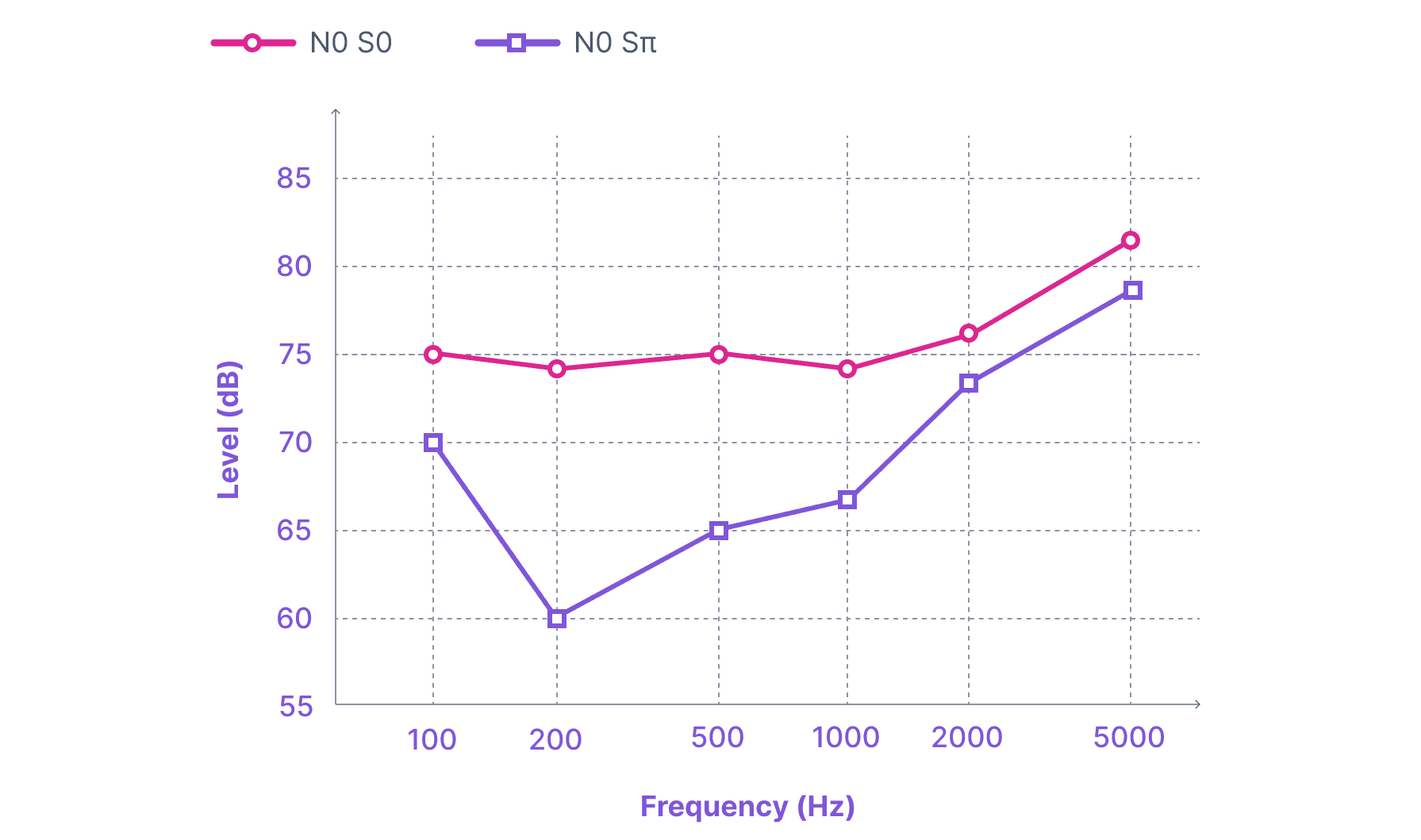

Binaural masking refers to the brain combining information from the two ears in order to improve signal detection and identification in noise. When we have the same signal and same noise coming into both ears we will most likely hear the tone with a certain threshold.

But if we introduce a phase-shifted tone on one of the ears the situation changes dramatically.

The threshold of hearing the specific sound in the midst of noise increases by 15dB. The sound is therefore perceived better, with more distinction than before.

Conclusion

Although this is a brief and condensed summary of the principles and basics of sound and Psychoacoustics, the knowledge gained in this paragraph allows us to move forward in the journey of discovery of music branding, conscious that the basic principles will become useful when entering “vertical” conversations about music branding or sound in general.

-

1.

➚

Cook, P. R., & MIT Press (Eds.). (1999). Music, Cognition, and Computerized Sound. MIT Press.

Plack, C. J. (2018). The Sense of Hearing. Routledge.

Plack, C. J. (2018). The Sense of Hearing. Routledge.