The psychology of music, or music psychology as it is also known, has a rich history beginning with the ancient Greeks. Pythagoras (580–500 BCE) undertook a series of experiments with a monochord that laid the foundation for music theory and the inclusion of music as a mathematical science alongside arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy in the early Greek education system. Modern music psychology evolved in the nineteenth century, with a focus on sound properties, as well as the measurement and nature of musical ability. Since the 1960s, the area has expanded to encompass studies of music perception (especially pitch, rhythm, harmony, and melody) and how we react to it. Recently, there has been a focus on the impact of music on our emotions, how we engage with music in our daily lives, and the broader advantages of music to our health, well-being, and cognitive functioning.1

Whenever we listen to some music or pieces of conversation, are we always conscious of what processing our auditory and processing systems are going through? Most of the things we hear are processed autonomously and without even requiring our attention.

In a 1993 study called The Effect of Background Music on Ad Processing: A Contingency Explanation researchers expose a fundamental truth for the world of audio advertising by stating: “Though most of the research literature has focused on emotional responses to ad music, it is also important to consider music’s impact on message reception and processing. Creative positive feelings during ad exposure may be desirable but have little impact unless the brand and message are remembered”2

Kellaris, Cox & Cox in the 1993 above cited study after analyzing why support is mixed when it comes to proving that music increases ad memorability, they introduce an important variable called music-message congruency. The term refers to “the congruency of meanings communicated nonverbally by music and verbally by ad copy”. Music can convey meanings in two distinct ways.

- It can convey a literal meaning by imitating a sound (e.g. birds calls, traffic noises).

- Music can convey images, thoughts and feelings even if they are more abstract.

Music-message congruency is then the “extent to which purely instrumental music evokes meanings that are congruent with those evoked by ad messages.”3 Another study conducted by Kellaris and Kent in 1993 called An Exploratory Investigation of responses Elicited by Music Varying in Tempo, Tonality, and Texture examines three dimensions of response to music (pleasure, surprise and arousal) elicited by three musical properties (tempo, tonality and texture). The goal of the experiment was to try to lay the foundation for some specific guidelines when designing certain pieces of music destined to be used for commercial purposes. In the research, for example, Kellaris and Kent notice that faster tempi produces greater arousal among subjects exposed to a piece of pop-music.4

Since ancient Greece, music has been related to emotions, and recent research demonstrates that people listen to music to attain varied emotional outcomes. Music can elicit a wide range of feelings, from simple arousal and 'basic' emotions like happiness and grief to more 'complex' emotions like nostalgia and pride. Even so, music does not necessarily elicit an emotional response. In fact, preliminary findings suggest that music only 'moves' us in around half of the episodes with music. Unfortunately, there is no theoretical understanding of which circumstances are more likely to elicit an emotional response and which are not. As a result, one of the ongoing key issues in this field is identifying the elements that influence emotional responses to music.5

Before the development of digital imaging techniques that allow us to understand how the brain performs various activities, most of the understanding about where music is processes derived from a post-mortem neurological examination of individuals that suffered from traumatic events such as strokes and functional losses.

Thus, a lot of studies focus on acquired amusia, meaning the inability to recognize musical tones or to reproduce them. Amusia, also called tone deafness, can be congenital or be acquired sometime later in life (as from brain damage).

“When we listen to a piece of music, most of us at least do not consciously deconstruct the sounds into all their core elements; the total experience (“gestalt”) is everything. What we hear depends on context—the relationships between sound components—and music perception requires a rapid abstraction and analysis of multidimensional stimuli.”

A study called The Smell of Jazz: Crossmodal Correspondences Between Music, Odor, and Emotion encompasses the complexity of multi-sensorial experiences and tries to categorize them in order to understand them better. Based on a 2011 study,6 there are three different types of correspondences: structural, statistical and semantic.

Here’s the definition of each one of them:

- Structural correspondences arise because of similarities in the information being provided by the different senses; for instance, magnitude may be represented by neural mechanisms that are common across modalities (e.g., bright lights might be matched to louder sounds because they both cause higher firing rates in the brain).

- Statistical correspondences arise via statistical learning; regularities in the environment, such as the fact that larger objects tend to create louder sounds, would cause a corresponding internal link between senses

- Semantic correspondences are also learned, but relate to language; for instance, “high” pitches and “high” elevations use the same terminology, which could thus lead to an association between pitch and elevation.

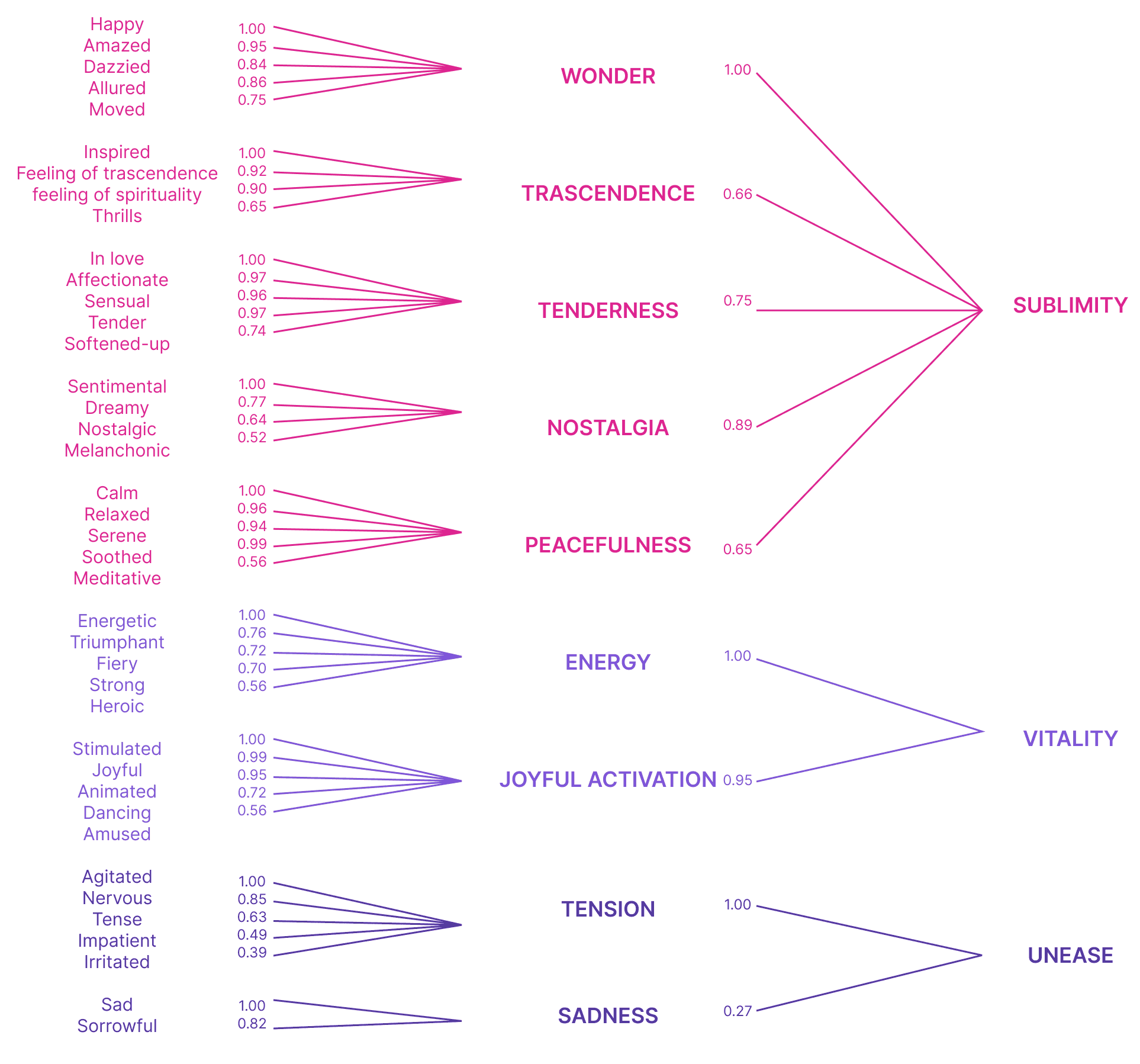

One of the most influential studies on music and emotions has been the GEMS (Geneva Music Induced Affect Checklist) from the University of Innsbruck. The GEMS is the world's first model and instrument dedicated to capturing the full range of musically evoked emotions. It's part of a larger effort to comprehend musically induced emotions. The GEMS model is based on a number of studies that used a variety of music and listener samples. There are nine different types of musical emotions in the model.

This domain-specific model more effectively accounts for music-evoked emotion ratings than multi-purpose scales based on non-musical fields of emotion research. Furthermore, they discovered that the experience of musical emotions tends to activate certain emotional brain areas. They also created the Geneva Emotional Music Scale as a complement to the concept (GEMS). The GEMS, which contains nine scales and 45 emotion descriptors, is currently widely utilized in music and emotion research. GEMS-25 and GEMS-9 are two shorter scales that have been designed.7

Conclusion

Needless to say, there is still a lot of research to be done in this field, but the latest academic results show that emotions play an important role in defining reactions to how music is perceived and experienced.

-

1.

➚

Hallam, S. (2019). The Psychology of Music. Routledge.

Kellaris, J. J., Cox, A. D., & Cox, D. (1993, October). The Effect of Background Music on Ad Processing: A Contingency Explanation. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 114-125.

Kellaris, J. J., Cox, A. D., & Cox, D. (1993, October). The Effect of Background Music on Ad Processing: A Contingency Explanation. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 114-125.

Kellaris, J. J., & Kent, R. J. (1993). An Exploratory Investigation of responses Elicited by Music Varying in Tempo, Tonality, and Texture. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 2(4), 381-401.

Juslin, P. N., Liljeström, S., Västfjäll, D., Barradas, G., & Silva, A. (2008). An experience sampling study of emotional reactions to music: Listener, music, and situation. Emotion, 8(5), 668–683.

Spence, C. (2011, January 19). Crossmodal correspondences: A tutorial review. Atten Percept Psychophys, 73, 971-995. 10.3758/s13414-010-0073-7

Trost, W., Ethofer, T., Zentner, M., & Vuilleumier, P. (2011, December 15). Mapping Aesthetic Musical Emotions in the Brain. Cerebral Cortex. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhr353